- Published: 6 May 2021

- ISBN: 9780241539606

- Imprint: Dorling Kindersley

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 256

- RRP: $24.99

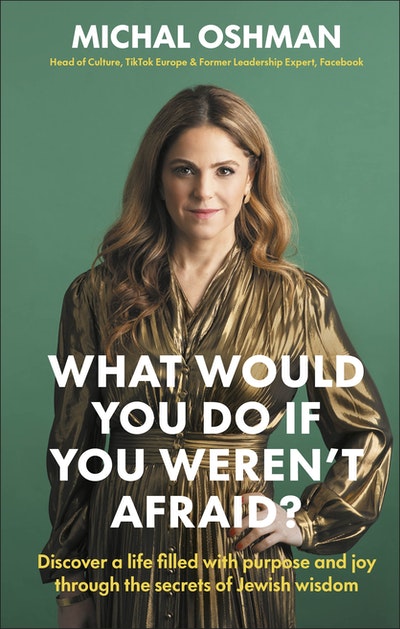

What Would You Do If You Weren't Afraid?

Discover A Life Filled With Purpose And Joy Through The Secrets Of Jewish Wisdom

Extract

The Search

My therapists explored my past – my childhood, and particularly my exposure to death. The Freudian model, on which they were trained, explains that mental illness is caused by events from our childhood. The focus is on the person’s past and the assumption is that they will resist growth and change, instead relying on patterns formed in their earliest years. My father’s job and the awful things I’d seen and heard, as well as the impact that the Holocaust had had on my family, were clearly – in my therapists’ eyes – the causes of my anxiety. It was helpful, to a certain degree, to reflect on childhood memories, but at some point, after many years of therapy, I realised that the therapy wasn’t going anywhere. We were revisiting the same stories, looking back through a blaming, limited lens.

Therapy became limited and limiting.

Don’t get me wrong – learning that my feelings followed a textbook pattern really did help to normalise my anxiety. But reliving the things I’d seen in my past became a never-ending cycle. It felt like picking a scab, scratching the same wounds over and over again.

Even though at times the wounds healed a bit, my therapists only seemed interested in digging up again the horrors I’d been exposed to and what they termed the ‘unfinished business’ with my parents. It got to the point where hearing the phrase ‘unfinished business’ really triggered me. It didn’t trigger me because I had unfinished business; it triggered me because I had actually resolved these issues after confronting my parents (which I talk about in greater detail in chapter two). Yet still the healing didn’t come and still the pain was there.

After going to therapy for many years, things had actually gotten worse, not better. But although I declared to myself that I was ready to give up on living a joyful life, deep inside me, I knew there was something else, something bigger than my anxiety, a spark of hidden joy that I just couldn’t get to. I didn’t know what the spark I felt inside was or how to reach it, but I believed it was there. And every time I tried to voice these feelings or ideas to my therapists, they would respond in exactly the same tone, with exactly the same phrases: ‘You are avoiding reality, Michal,’ ‘You’re looking for an easy way out, Michal,’ ‘You are looking to suppress your real issues, Michal.’ I realised my healing would not come from any therapist.

For a very short time, I turned to Buddhism. I read and educated myself, but I wasn’t ready to embrace Zen practices and I wasn’t able to let go of pain. Actually, I didn’t want to let go of my pain or to avoid it – I wanted to look it in the eye, I wanted to solve it. I tried a life coach. One day he asked me if, given the choice, I would choose to cut out the ‘anxiety part’ of me, to remove it as if it had never been there. In all my years of therapy I had never been asked such a powerful question. Would I? Would I want to completely get rid of the uncomfortable aspects of myself? Would I erase a whole part of me?

After several long minutes of reflection, I realised that the answer was a definite NO! I still think about this moment often. It was a turning point for me with regards to the way I viewed my anxiety.

Even though I suffered daily, I wanted to keep every part of myself, even the painful parts. Who would I be without my life experience? Would I become a different person? Ultimately, this baggage was part of what made me me. I just didn’t want to only look back. I wanted to look forward, too, to move towards something and find hope and potential. But I didn’t know the way. I decided that, instead of trying to wipe away all these parts of me, I would learn to understand myself through a new lens, using a completely different perspective to Western psychotherapy. But what was that other perspective? I just didn’t know.

It was around this time that I read a book by Viktor E. Frankl called Man’s Search for Meaning. Dr Frankl was a gifted student of Sigmund Freud and a champion of psychoanalysis during its heyday in the 1920s. Frankl was a well-known neurologist, psychiatrist and therapist who challenged Freud’s ideas. He started to disagree with Freud on a number of things, namely what really drives humans to act and think the way they do.

For Freud, the fundamental human drives are pleasure and self-preservation. But Frankl saw that humans had something else – a yearning for meaning in their life. He began to develop a theory of psychotherapy called logotherapy, which means ‘therapy of meaning’. Whereas Freud believed that happiness comes from the pursuit of pleasure and the avoidance of pain, Frankl believed that the more we pursue happiness, the less likely we are to find it. Instead, we should view happiness simply as a side effect of finding something we care about.

Happiness is not the goal itself – Frankl believed that humans are not simply seeking pleasure for its own sake, but are seeking meaning.

Dr Frankl came up with most of his findings during his time as a prisoner in the Nazi death camps where he was tortured, humiliated and nearly murdered on several occasions. He experienced incredible cruelty and was exposed to mankind’s ability to commit terrible crimes against their fellow human beings. But Dr Frankl also made a ground-breaking discovery. He saw prisoners holding on to life, even when death would have been a relief. But why? Why would someone want to survive, under horrific, hopeless, terrifying circumstances?

The answer he came up with was purpose.

What kept prisoners alive was their incredible internal drive to fulfil a unique purpose – a person to live for, a cause to support or a meaningful task to complete. There, in the horror of the concentration camps, Frankl discovered that finding purpose changes your outlook on life. It can even save your life.

This resonated powerfully with me, and not just because I had lived most of my life in the shadow of the Holocaust, hearing my grandparents’ stories, feeling their fears. Frankl’s ideas captivated me because I had already felt that small spark inside me and I knew that it was capable of growing into something more.

What Would You Do If You Weren't Afraid? Michal Oshman

TikTok and ex-Facebook leadership development coach Michal Oshman reveals the secrets to living a meaningful, successful and joyful life.

Buy now