- Published: 20 October 2020

- ISBN: 9781761040153

- Imprint: Penguin Life

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 224

- RRP: $32.99

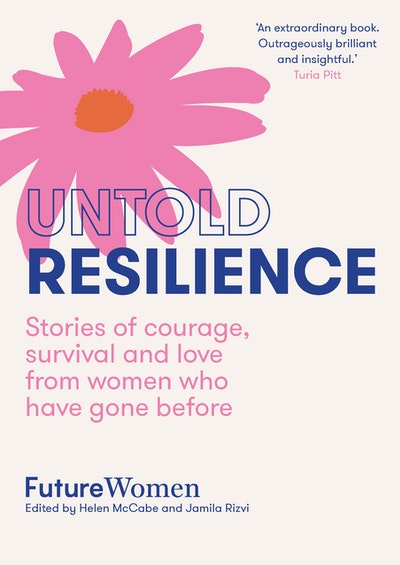

Untold Resilience

Stories of courage, survival and love from women who have gone before

Extract

Introduction

By Jamila Rizvi, Future Women

‘For young people who have never been through any of those things, or lived in a time when they were happening, this seems just frightful . . . But if you’ve witnessed, heard about and know people who’ve been through these other things, you think, “Well, we’re going to make it through this.”’ – Margaret Atwood

It was Booker Prize-winning author and international treasure Margaret Atwood who did it. It was her fault I found myself sitting on the bathroom floor with my back against the door (to block my insistent four-year-old from entering). I’d been listening to her speak on the popular Dear Sugar podcast when she said the words inscribed above. In that moment, my previously stalwart efforts to avoid giving in to pandemic grief began to fail. I sat there beside the toilet, my poor old bum soaking in the coldness of the tiles, and sobbed until there was nothing left inside.

My coronavirus isolation happened hard and fast. The night before, I’d been at a Future Women event full of smart, diverse and very funny women. While guests had avoided the standard hug-and-kiss greeting, the room was still absolutely packed. This was a sell-out crowd. There were more than 250 people in the audience, each sitting quietly side by side, captivated by the speakers on stage. We were moved and humbled. Now, when I think about that audience’s prolonged proximity to one another, I cringe.

The next day, my husband and I made the decision to bunker down. I have a series of chronic conditions that make me particularly vulnerable to illness. In the early days when people were casually saying things like, ‘It’s only sick and old people who will die from the coronavirus,’ I was one of those whose death was apparently acceptable. I needed to stay safe and, for that to happen, my family needed to keep themselves safe as well. We agreed that over the weekend we’d make the necessary preparations to self-isolate, suspecting that everyone would be joining us sooner or later.

And then my husband got sick.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that nobody experiences a cold quite like a man, and the one I married embodies this cliché. But this was no ordinary seasonal sneeze-fest. Jeremy had a high temperature, chills and a horribly sore throat. He had shortness of breath, aches and pains in his limbs and the most horrendous-sounding wet, rasping cough.

In the early days of the pandemic the criteria for testing was tight, unlike now. Australia didn’t have enough tests to go around and we didn’t know how bad the situation was going to get. Despite multiple visits to the doctor, Jeremy never qualified for the infamous nasal swab.

And so, our pandemic plan went into action earlier than anticipated. My son was away with his grandmother at the beach and we asked if he could stay there. We didn’t want either of them exposed. Not seeing our little boy for weeks was genuinely tough. Jeremy stopped leaving the house at all and confined himself to our bedroom. I started sleeping in another room and left the house only occasionally, in search of caffeine, groceries and Codral. Every waking minute that I wasn’t working or on FaceTime to my son was spent cleaning. I sterilised everything Jeremy touched. I was like the lady on the Spray n’ Wipe advertisement, who just loves scrubbing things until they sparkle. Bleach became my best mate.

Jeremy recovered slowly, though even after four weeks this fit and healthy man in his thirties still got puffed walking up the stairs. We’ll probably never know whether the coronavirus arrived in our home in March 2020 but thankfully nobody else in the family got sick. In the meantime, of course, the entire nation had been sent home. New restrictions were declared and updated repeatedly, and fines for breaking the rules increased. A national cabinet was formed, stimulus packages were announced and workers were laid off. Far fewer people left their homes to go to work. Neighbourhoods felt eerie and empty, despite kids being pulled out of school. Oh, and everyone started hoarding toilet paper.

During the ensuing months, a terrifying global picture was painted in real time on our smartphones and laptops. We no longer waited for the nightly news because updates were urgent and often. We felt nervous whenever alerts sounded on our phones and yet we compulsively read every new story that appeared, desperate for the next morbid update. We watched as people died around the world. First China, then Italy, then South Korea, the USA, and then . . . everywhere. Hundreds of thousands of lives lost. Many died without access to the health care that might have saved them. At home in Australia, unemployment figures were climbing steadily. Each meagre percentage point represented hundreds of thousands of real people and their families.

I was one of the lucky ones. While money got tighter in some ways, savings were made because we no longer went anywhere or did what we’d usually do. The household remained financially secure and we were physically safe. Family and friends experienced a different and more frightening new normal where changed economic circumstances left them questioning how they’d get by. Loved ones on the other side of the world faced the confronting reality of attending virtual funerals and wondering who might die next. People living in developing countries or housed in close proximity in refugee camps had little to no chance of being able to physically distance. How do you prevent spread when there is one water source for every 20,000 people and soap is a rarity?

I’m a somewhat anxious person. My mum calls me a worrier. But I suspect that I found isolation easier than I otherwise might have because previous illness had left me stuck at home for long periods of time. Despite being a ferocious extrovert, I was used to the slower and quieter pace of life. I was busy with work, I felt safe in my home and well, who was I to be upset and struggling? I wonder if you felt the same. Almost as if you were unworthy of fear and panic when there were others doing it far tougher. It’s a strange sort of grief: anxiety over an undetermined future, and your heart hurting for people you would never, and now will never, meet.

From the outset of the pandemic, I wanted to speak to my nan. Her name was Margaret Mary Bowes, but everyone had known her as Peg. A mother of three children, and grandmother to nine, Nan’s life was shaped by the times she lived in. She was a clever child who skipped lots of grades and won scholarships. Mathematics was her speciality. She could run off times tables up to and beyond fifteen and worked in metrology during the war, which involved measurement and calibration. After getting married Nan had to give up her job, but found work in a post office for a time. Once she had children, family became – and remained – her number one priority.

Nan set off to university later in life, determined to get a degree because she was ‘sick of staying home and looking at gum trees’. Graduating in her sixties, she said the hardest thing about her arts degree was finding her car in the packed parking lot after classes. She was always grateful to Prime Minister Gough Whitlam for her free education. I remember Nan as a ferocious reader, incredible cook, impeccable sewer and kind in that no-nonsense sort of way that women of her era tended to be. Women who’d lived through more difficult times.

My memories are understandably of the later years of my Nan’s life. Born in 1924, she was a child of the Depression and lived through World War II. In hospital, during the final weeks of her life, she told me horror stories of the polio and tuberculosis pandemics. She was forced to spend many months at home to stay safe and was devastated to miss out on school. In the days before her death, she was as sharp as ever, railing against anti-vaccination proponents. ‘They don’t know what it was like,’ she explained to me, sipping the evening glass of Scotch that’s apparently mandatory in a hospice.

Nan died in 2013. Before MERS, the Ebola breakout of 2014 and of course, before COVID-19. In those self-indulgent minutes spent on the bathroom floor in the middle of March 2020, I desperately tried to draw on her wisdom and resilience. I wanted her assurance that people had survived worse and we would survive this too. I imagined Nan’s firm but warm voice telling me that despite the present terror, and future terrors that likely lay ahead, we’d be all right in the end. It’s a perspective that comes only from having been there before – the kind of perspective Margaret Atwood described.

I needed a compass of personal fortitude, someone who could give me direction and perspective in the midst of this bewildering global crisis that threatened to swallow my sensibility entirely. There were so many ‘what if’s, not just for me and the people I cared about but for humanity as a whole. The problem felt so inconceivably large, and with no ‘end’ in sight I was losing my grip on what was real and what was not. When the President of the United States is suggesting their citizens drink bleach while others are dying on stretchers outside of hospitals, realism seems rather relative. Were we really living in a disaster movie? I wanted someone sensible – someone who had been here before – to tell me I should relax and that humans have survived worse.

When Helen McCabe founded the digital platform Future Women, she wanted its membership to reflect an attitude, not an age. Meeting and talking to the incredible women whose stories are contained in these pages has made me understand what Helen meant. Occasionally these incredible individuals’ experiences have felt like something from another world, not simply another time or another country. Some of them have survived the impossible. And yet, I felt a shared spirit with the women we interviewed, and a sense of common values. We could have been close girlfriends had we been born into the same generation, I’m sure. I both admired and felt kinship with them. Future Women is privileged to share the love and wisdom of these women – their lives and lessons – with a new generation. All of you.

The work of collecting these stories has been deeply personal for both the journalists and their interview subjects. The continued dangers posed by the coronavirus pandemic, particularly for older people, has meant none of our journalists could meet face to face with the women whose stories they were telling. At first we were hesitant to embark on such an ambitious project, the success of which hinged on trust and honesty between storytellers. We needn’t have worried. Despite distance, age gaps and varied life experiences, our journalists each formed a devoted bond with the women whose stories are contained within these pages. Personally, I cannot wait until I’m able to hold the hands and look into the eyes of the women who so generously shared their lives with me – and say a sincere thank you.

Before now, several of these remarkable women have only ever told their stories through the prism of the men in their lives. Indeed, there were moments when our interviewers found themselves struggling to draw out the stories of the women themselves, and not the men they had loved. History celebrates the brave wins and noble losses of men, but rarely pays mind to the sometimes quieter, intelligent determination of women; women who were fighting courageously for their survival at the same time, in different ways. This book makes a small contribution to setting that skewed presentation of history right. It pays homage to the extraordinary experiences of women who sought no medals and who gave no aggrandizing speeches. These are women who put their heads down and got the job done, proving their strength through the steadfastness of their actions.

I cannot wait for you to meet them.

Untold Resilience Future Women

A timely and uplifting book of true stories from 19 women whose resilience has seen them survive extraordinary global and personal tragedy.

Buy now