- Published: 29 September 2020

- ISBN: 9781784164980

- Imprint: Black Swan

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 272

- RRP: $22.99

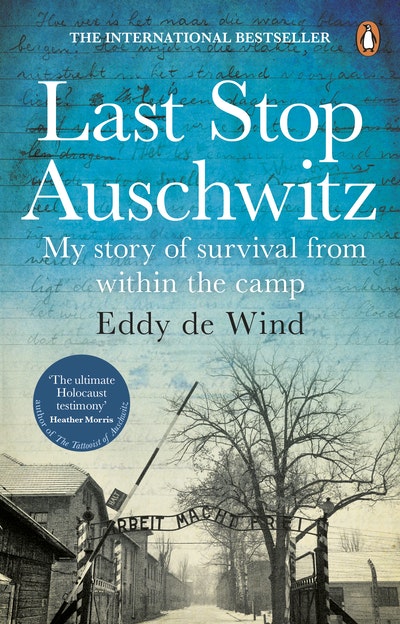

Last Stop Auschwitz

My story of survival from within the camp

Extract

In 1943, Jewish doctor Eddy de Wind volunteered to work in Westerbork, a transit camp for the deportation of Jews in the east of the Netherlands. From Westerbork inmates were sent on to concentration camps, including Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen. Eddy had been told that his mother would be exempted from deportation in exchange for his work – in fact she had already been sent to Auschwitz. At Westerbork, Eddy met a young Jewish nurse called Friedel. They fell in love and married at the camp.

In 1943, they too were transported to Auschwitz and were separated: Eddy ended up in Block 9 as part of the medical staff, Friedel in Block 10, where sterilization and other barbaric medical experiments were conducted by the notorious Josef Mengele and the gynaecologist Carl Clauberg.

Somehow, both Eddy and Friedel survived.

When the Russians approached Auschwitz in the autumn of 1944, the Nazis tried to cover their tracks. They fled, marching their many prisoners, including Friedel, towards Germany. These Death Marches were intended to eradicate all evidence of the concentration camp’s atrocities.

Eddy hid and remained in the camp; it would take months before the war ended. He joined the Russian liberators. By day, he treated the often very ill survivors the Nazis had left behind and also Russian soldiers. By night, having found a pencil and notebook, he began to write with furious energy about his experiences at Auschwitz.

In his traumatized state, he created the character of Hans to be the narrator of his own story. Other than in a few instances, the horror of his experience was still so raw he couldn’t find the words to describe it in the first person. This is Eddy’s story.

How far is it to those hazy blue mountains? How wide is the plain that stretches out in the radiant spring sunshine? It’s a day’s march for feet that are free. A single hour on horseback at full trot. For us it is further, much further, infinitely far. Those mountains are not of this world, not of our world. Because between us and those mountains is the wire.

Our yearning, the wild pounding of our hearts, the blood that rushes to our heads – they are all powerless. Because of that wire between us and the plain. Two parallel fences of highvoltage barbed wire with dim red lights that glow above them as a sign that death is lurking there, lying in wait for all of us imprisoned here in this rectangle enclosed by a tall white wall.

Always the same image, the same feeling. We stand at the windows of our blocks and look into the enticing distance while our chests heave with tension and impotence. We are ten metres away from each other. I lean out of the window while longing for that faraway freedom. Friedel can’t even do that, her imprisonment is more complete. I can still move freely through the Lager. Friedel can’t even do that.

I live in Block 9, an ordinary hospital block. Friedel lives in Block 10. There are sick people there too, but not like in my block. Where I am, there are people who have fallen ill from cruelty, starvation and overwork. Those are natural causes that lead to natural diseases that can be diagnosed.

Block 10 is the experimental block. The women who live there have been violated by sadists who call themselves professors, violated in a way that a woman has never been violated before, violated in the most beautiful thing they possess: their womanhood, their ability to become mothers.

A girl who is forced to submit to an uncontrolled brute’s savage lust suffers too, but the deed she endures springs from life itself, from life’s urges. In Block 10 the motive is not an eruption of desire – it is a political delusion, a financial interest.

All this we know as we look out over this plain in the south of Poland and long to run through the fields and marshes that separate us from the hazy blue Beskid Mountains on the horizon. But that is not all we know. We also know that for us there is only one end, only one way to be free from this barbed-wire hell: death.

We know that death can come to us here in different forms.

He can come as an honourable foe that a doctor can fight. Even if this death has base allies – hunger, cold, fleas and lice – it remains a natural death that can be classified according to an official cause. But he won’t come to us like that. He will come to us just as he came to those millions who have preceded us here. When he comes, he will almost certainly be stealthy and invisible, almost odourless even.

We know that only subterfuge hides death from our view. We know that this death is uniformed because the gas tap is operated by a man in uniform: SS.

That is why we yearn so, looking out at those hazy blue mountains, which are just thirty-five kilometres away, but for us eternally unattainable.

That is why I lean so far out of the window towards Block 10, where she is standing.

That is why her hands grip the wire mesh on her window so tightly.

That is why she rests her head on the wood, because her longing for me must remain unquenched, along with our yearning for those tall, hazy blue mountains.

The young grass, the swollen brown chestnut buds and the radiant sun that was growing more glorious with every passing day seemed to promise new life. But the Earth was covered with the chill of death. It was spring 1943.

The Germans were deep in Russia and the fortunes of war had yet to turn.

In the West, the Allies still hadn’t set foot on the Continent.

The terror raging over Europe was taking fiercer and fiercer forms.

The Jews were the conquerors’ playthings. It was a game of cat and mouse. Night after night, motorbikes roared through the streets of Amsterdam, jackboots stamped and orders snarled along the once so-peaceful canals.

Then, later, in Westerbork, the mouse was often released for a moment. People were allowed to move freely around the camp, packages arrived and families stayed together. Everyone wrote an obedient ‘I am fine’ letter to Amsterdam, so that others in turn would also surrender peacefully to the Grüne Polizei.

In Westerbork the Jews were given the illusion that everything might not turn out too badly, that although they were now excluded from society, they would one day return from their isolation.

‘When the war is done and everyone

Is on the way back home . . .’

was the start of a popular song.

Not only did they not see their future fate, there were even some who had the courage – or was it blindness? – to start a new life, to found a new family. Every day Dr Molhuijsen came to the camp on behalf of the mayor of the village of Westerbork, and one magnificent morning – from April’s quota of nine fine days – Hans and Friedel appeared before him.

They were two idealists: he was twenty-seven and a wellknown doctor at the camp; she was just eighteen. They had got to know each other in the ward where he held sway and she was a nurse.

‘Because alone we are none,

But together we are one.’

he had written in a poem for her, and that was exactly how they felt. Together they would win through. Maybe they would manage to stay in Westerbork until the end of the war, and otherwise continue the struggle together in Poland. Because one day the war would end and a German victory was something nobody believed in.

They were together for half a year like this, living in the ‘doctor’s room’, a cardboard box in the corner of a large barracks with one hundred and thirty women. They didn’t have the room to themselves, but shared it with another doctor and, later, two other couples. Definitely not the appropriate surroundings for establishing a young married life together. But none of that would have mattered if there hadn’t been a single Transport: one thousand people every Tuesday morning. Men and women, young and old, including babies and even people who were ill.

Only a very small number were allowed to stay behind, when Hans and the other doctors were able to prove that they were too sick to spend three days on a train. Also exempt were those with a privileged status: the baptized, the mixed marriages, alte Kamp-Insassen who had been interned since 1938, and permanent members of staff like Hans and Friedel.

There was a staff list of a thousand names, but there was also a steady influx of new arrivals from the cities who needed to be protected, sometimes on German orders, sometimes because they really had been worthy citizens, but mostly because of longstanding connections with the notables on the Jewish Council or with the alte Kamp-Insassen, who had a firm grip on the key positions in the camp. Then the list of one thousand would be revised.

This was how it came about that an employee of the Jewish Council came to Hans and Friedel on the night of Monday, 13 September 1943 to tell them that they had to get ready for deportation. Hans dressed quickly and made a round of all the authorities, who worked under high pressure on the night before the weekly transport. Dr Spanier, the head of the hospital, was furious. Hans had been in the camp for a year. He had worked hard; there were many others who had arrived later and never done a thing. But Hans was on the Jewish Council staff list and if they couldn’t keep him on it, the health service couldn’t do anything about it either.

At eight o’clock they were standing with all their belongings next to the train, which ran through the middle of the camp. It was tremendously busy. The camp police and the men of the Flying Column were carrying baggage to the train and two wagons were loaded with provisions for the journey. The male nurses from the hospital came trailing up with the patients, mostly elderly, who couldn’t walk. That wasn’t sufficient reason to let them stay – next week they would be no more mobile than they were now. Also present were friends and family who were staying in the camp; they stood behind the cordon, twenty or thirty metres away from the train, often crying more than those who were leaving.

At the front and back of the train were carriages with SS guards, but they were very fair, and tried to keep people’s spirits up, because it was essential to keep the Dutch from finding out how ‘their’ Jews were really being treated.

Half past ten: departure. The doors of the goods wagons were bolted on the outside. A last goodbye, a last wave through the hatches in the roof of the wagon, and then they were on their way to Poland, exact destination unknown.

Hans and Friedel had been lucky and were in a wagon with only young people, old friends of Friedel’s from the Zionist group she had belonged to, friendly and accommodating. Altogether there were thirty-eight of them. That was relatively few and, with a little reorganization, hanging baggage from the ceiling, there was room for them to all sit down on the floor.

The fun and games started during the trip. At the first stop, SS men came into the wagon demanding their cigarettes, and later their watches. The next time it was fountain pens and jewellery. The lads laughed it off, giving them a few loose cigarettes and claiming it was all they had. A lot of them were originally German; they’d had dealings with the SS often enough before. They’d come through it alive then too, and they weren’t going to let themselves be bullied around this time either.

They weren’t given any food in those three days and they never saw the train’s provisions again. But that didn’t matter! They still had enough with them from Westerbork. Now and then a couple of them were allowed to leave the wagon to empty the small and overflowing toilet barrel. They were delighted when they saw signs of bombing raids in the cities, but otherwise the trip was uneventful. On the third day they found out their destination: Auschwitz. It was just a meaningless word, neither good nor bad.

That night they reached the Auschwitz railway yard.

Last Stop Auschwitz Eddy de Wind

An Auschwitz prisoner's remarkable account of suffering and survival, an international bestseller and the only complete book written inside the camp.

Buy now