- Published: 1 April 2015

- ISBN: 9781742759869

- Imprint: Bantam Australia

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 528

- RRP: $22.99

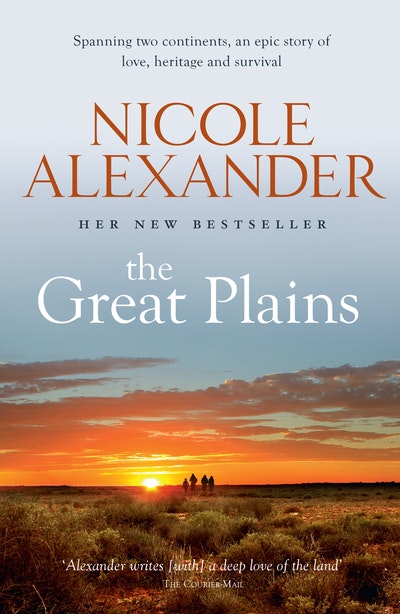

The Great Plains

Extract

Thirty-nine years earlier September, 1886 – Dallas, Texas

Aloysius Wade looked down at the main street of Dallas from the second-storey window of Wade Newspapers. Timber shops and business houses lined the wide dirt road. Men on horseback fought for space with covered wagons, drays and sulkies as full-skirted women lifted their hems above rain puddles. At the far end of the street a wagon laden with buffalo bones was halted outside the hotel. The pieces of skeleton glinted in the late morning sun as a black child in cut-off pants and bare feet stood guard, perched on a wagon wheel.

Dallas had once been the world centre for the trade of leather and buffalo hide but with the animal practically wiped out, the desperate were gathering the sun-whitened bones of the slaughtered beasts and selling them to ?ll the demand for fertiliser back east. Aloysius had brie?y considered entering the market, but his head had been ?lled with images of bedraggled men, women and children scouring the carcass-strewn plains. Collecting the bones of the dead was not a legacy he fancied even if there was substantial coin to be made.

He still couldn’t help but marvel at the growth the city had undergone over the past three decades. His father had ?rst sent him and his older brother, Joseph, west to Dallas in 1857 with a view to making men out of them under the guise of expanding the family business. At that time Aloysius had held little hope of a successful venture. The brothers expected to be killed en route either by Indians, accident or some other wily character. As it was, one of their wagons was lost crossing the Red River.

There had been less than six hundred inhabitants on arrival, which Joseph considered to be an impressive population considering a few years earlier a trading post had been the only feature. The streets were orientated to a bend in the Trinity River at the site of a limestone ledge, which was meant to be the head of navigation. In fact the river was unnavigable but it was the best crossing for miles and Aloysius and Joseph grew used to seeing the billowing clouds of dust that signi?ed hundreds of head of cattle being driven along the Shawnee Trail. Dallas had grown on the back of farming and ranching, but it was only with the arrival of the railroads that the city had prospered.

‘Mr Wade, sir.’

Aloysius greeted his assistant brusquely. Fifteen-year-old Hugh Hocking was the son of his closest friend, Clarence, who was also his accountant and advisor.

Hugh placed the day’s mail on Aloysius’s desk. ‘My father called regarding the State Fair.’

‘And?’

A single ri?e shot echoed in the distance. Aloysius reached automatically for the colt holstered at his hip.

Hugh ?inched. ‘He’s on his way, sir.’

Aloysius turned to resume his perusal of the street as Hugh exited the room. The heady days of shoot-outs in the main street were almost as rare as feathered frogs, but there were still scrapes between liberated slaves and whites. And there was invariably the odd drunken cowboy or old Indian who came into town to pick a ?ght. Only last week a black had been lynched on the outskirts of East Dallas for insulting a white woman. The Civil War had changed much and Aloysius knew many southerners wished Dallas had perhaps not been so prosperous at the end of the war compared to other southern cities, although the in?ux of blacks meant there was rarely a shortage of domestics or ?eldworkers, even if they did have to be paid.

The war. Aloysius couldn’t think or speak the phrase without remembering his older brother, Joseph. On impulse, he opened the top drawer of his desk and reached for the letter Gregory Harrison had written in 1863 from Fort Sumner. Gregory, an old friend from their Charlestown days, had been killed a few months later, shot through the heart by a Kiowa Brave. Aloysius re-read the letter, as he had every week for the past twenty-three years. It was the last time his niece’s name had been written in ink. Philomena was presumed dead.

We are now facing renewed hostility from the Apache and assume from previous engagements that retribution will be ?erce. On that front I was most sorry to hear of your grievous news. In answer to your investigations my advices suggest that it was indeed Geronimo or one of his band who captured your niece, Philomena. The girl’s abduction following the murder of her brother and father is now well-documented in these parts and, although missives have been sent in an effort to broker her return, there is no news.

Aloysius had spent a lifetime revisiting the events that had led to his brother’s death. At the outbreak of war he’d argued with Joseph for the right to join the Confederate Army. Their father had forbidden them to both enlist in an effort to protect the family line. Joseph eventually grew tired of quarrelling with his younger brother and they agreed to toss a coin to see which of them would go to war. Joseph won.

A sharp knock on the door broke Aloysius’s re?ections and he replaced the letter in the drawer. Straight-backed, of medium height and brown hair, in middle age Clarence Hocking veered towards being overweight. In comparison, Aloysius in his forty-ninth year remained slim and ?t. He rode to work every day and took a constitutional along the banks of the Trinity River after lunch when time permitted. After pleasantries were exchanged, Clarence came straight to the point and handed Aloysius a copy of the ?nancials for Dallas’s inaugural State Fair. Due to open next month, Aloysius was part of the private corporation behind the venture. He and his partners were hoping for crowds that would edge the 100,000 mark, thereby ensuring a healthy pro?t. Aloysius checked the ?gures.

‘I have no doubt that we will exceed our projections, Aloysius,’ Clarence explained. ‘We certainly have the necessary transportation in place to bring the masses to our fair city.’

‘Yes, well we are all agreed on that. The railroad has made this town. Believe me, there was a time when I had my doubts as to my father’s sanity when he sent Joseph and I out here.’

Clarence Hocking shuf?ed papers and slid another document across Aloysius’s desk. ‘And in all deference to your father, I too was a little perturbed when he asked me to join you.’

‘Well, it certainly worked out well, for both of us.’

Hocking’s mouth twitched. It was the closest he ever came to a smile. Five years older than Aloysius, he’d been a widower on arrival, but he’d quickly remarried and fathered seven children, all of whom had survived and most of whom were law-abiding. The hopes of the family lay with Hugh, who’d shown himself to be intelligent and hardworking. Hocking pointed to the document sitting on the desk. ‘I have copies of the pro?t and loss statements for Wade Mercantile and Wade Grocers & Provisions. Did you want me to run through them?’

‘Are my sons making a pro?t?’ Aloysius enquired, checking the rows of ?gures.

‘Joe is overseeing the mercantile end of things very well but, of course, like most businesses everything is on credit. As long as the farmers are productive he’ll be paid in due course. And he seems to be managing the plantation well.’

‘The costs of shipping to the coast are too high,’ Aloysius commented. ‘If the cotton prices ever dropped signi?cantly . . .’

Hocking agreed. ‘Exactly, which is why Dallas must continue on its path to becoming a self-sustaining industrial city.’

Aloysius had been one of the earlier owners to see the bene?t of sharecropping following the changes wrought by the Civil War. Both free black farmers and landless white farmers worked on the Wade plantation in return for a share of the pro?ts, and the arrangement was proving lucrative for the family, although many a time it would have been far simpler to revert to the old ways and simply ?og the Negroes who got uppity. Diversi?cation remained the signature reason for the Wade family’s success. It was Aloysius who convinced his father to extend their interests beyond newspapers and into farming and retail a few years after their arrival at Dallas, while Joseph had travelled to New Mexico to investigate the tin and silver mines. Their early business ventures had also been signi?cantly buoyed by two prudent marriages. ‘What about Edmund? Has my youngest lad reached the agreed sales ?gures?’

Clarence gave a sigh that assumed a father’s disappointment. ‘Frankly the store should be doing a lot better. Settlers are passing through Dallas and heading north into Indian Territory in greater numbers every year. The trade for goods and provisions should be rising accordingly.’

Aloysius selected some newspapers from a side table and spread them across the desk. ‘The Civil War and subsequent restructuring of the South continues to affect many.’ Aloysius pointed at the newspapers, the Cherokee Advocate, the Indian Journal, the Indian Citizen. ‘All of these tribal newspapers talk of the in?ux of white and black farmers into Indian Territory. The Indians are making a fortune leasing their lands or sharecropping them. Why, the Cherokee lease their six-million-acre Outlet to the Cherokee Strip Live Stock Association of Kansas for 100,000 dollars annually. We’re talking 300,000 head of cattle on Cherokee rangelands.’

Clarence shook his head. ‘I’m not moving to Indian Territory, if that’s what you’re suggesting.’

‘I’m simply saying that there are many in?ationary and de?ationary pressures affecting people since the war. People are looking for a new start. Edmund should be taking advantage of the situation. You mark my words, the civilising of the West has just begun.’

Clarence couldn’t fault his old friend’s argument. The massacre of buffalo by the military, who knew that the extinction of the animal might well result in the destruction of the Indians by depriving them of a signi?cant part of their culture, had led to an increase in cattle. And while Clarence still owned a ranch, the days of open-land ranching with corrals and cowboys had swiftly changed with the arrival of barbed wire. Cropping farms were increasing and overseas capitalists were making substantial investments in the cattle industry.

‘The government won’t let the tribes keep their land when there are good honest folk willing to make a living.’ Aloysius thumped the table with his ?st for emphasis. ‘Why, those savages shouldn’t have any rights at all. If there is money to be made, we’re the ones who should be making it. I still think back to the June of 1876 when we heard of General Custer’s slaughter at the Battle of Little Big Horn and, to this day, I can see no good reason for any Indian to be accorded land or rights.’

Clarence waited as his old friend calmed. ‘And how will the Indians make a living? I seem to recall them being here ?rst.’ Purple was not quite the word for the colour Aloysius’s face had turned but it was close. Clarence was aware he shouldn’t taunt his friend, not when he knew ?rst hand of Aloysius’s obsession with his abducted niece. He was, however, one for giving his word and keeping it. The Indians had been assigned lands by the government of the day, lands where they could hopefully make a living and live quietly. Clarence considered this a fair result. After all, they may well be savages but one could hardly act like they didn’t exist. ‘My apologies, Aloysius, we have differing views on this subject.’

‘A place for everyone, eh, Clarence? Yes, yes, but as far as I’m concerned the only good Indian is a dead Indian.’

‘Well, in the meantime we have the problem of your son to address. Might I suggest we promote the Harbison lad to store manager and perhaps Edmund should join the newspaper? He’s not been the same since Jenny’s death.’

Aloysius was not immune to Clarence’s placating tone. Gathering up the newspapers, he sat back at the desk, his gaze wandering absently over the framed headlines from the earliest editions of the newspaper. Edmund, Aloysius’s youngest son, had been slow to mature and even slower to marry. With his wife dying in childbirth along with their hoped-for ?rst child a year earlier, it was time the lad selected a new bride and got down to the business of successful breeding. ‘He needs a wife. There’s nothing like children to keep a man at the of?ce. God knows, Annie and I managed three girls and two sons, which was enough to keep my nose to the mill.’

‘So you’ll speak to him?’ Clarence con?rmed.

‘I daren’t send him out to the plantation or the farm. He’d be just as likely to give half the cotton and wheat we produce away.’ Aloysius poured two whiskeys from the cut-glass decanter on his desk and slid a tumbler across to his old friend. ‘What? You’ve got that look in your eye, Clarence, like you’re intending on a lecture.’ Aloysius took a sip of the strong spirit.

‘I was thinking about the past, speci?cally your family’s,’ Clarence swallowed the whiskey in a single gulp. ‘I know how much you hate the Indians.’

‘Apaches, I hate the god-damn Apaches, and I’ve every right. Twenty-three years, Clarence, and not a single word,’ he replied, clutching the glass.

‘Until today.’

Aloysius sat forward in his chair, a lock of greying hair fell across his brow. ‘What are you talking about?’

Clarence withdrew an envelope from his coat and held it across the desk. ‘The letter came to my of?ce,’ he stated by way of explanation. ‘Geronimo has surrendered.’

Aloysius stared at his old friend as if the contents could be discerned from the intelligent eyes opposite him.

Clarence sat the letter on the desk. ‘A Captain Henry Lawton and First Lieutenant Charles B. Gatewood have led an expedition that has brought Geronimo and his followers back to the reservation.’

Aloysius reached for the envelope, ?icked open the broken seal and unfolded the paper. ‘Why didn’t you tell me of this immediately?’

‘Because wanting something doesn’t mean it will happen,’ Clarence replied. ‘There was a white woman with the Apaches.’

Aloysius stood, his chair falling backwards to land with a loud thud on the timber ?oor. He scanned the contents of the letter.

‘The similarities are strong,’ Clarence said evenly, ‘but obviously we cannot be assured that the woman mentioned is –’

Aloysius tapped at the letter. ‘They say she is blonde-haired, striking in appearance,’ his eyes grew misty, ‘and aged in her thirties.’

‘The details are compelling, I admit, but I urge you, my friend, not to get your hopes up,’ Clarence replied carefully.

‘It’s her. It’s Philomena.’ Aloysius’s voice grew tight with emotion.

‘I know how long you have prayed for this moment, Aloysius, but the probability that this woman is indeed your niece remains slight.’

The single sheet of paper trembled between Aloysius’s ?ngers. ‘They have found my dead brother’s daughter.’ He looked to the ceiling. ‘God be praised.’

‘If it is her,’ Clarence cautioned, ‘if it is indeed your niece, as your friend I can only advise you to temper your happiness until you learn the true nature of her state.’

Aloysius frowned. ‘What rubbish are you speaking of, Clarence?’

‘It is over twenty years since her abduction.’

‘And I have never stopped thinking of the child. She is my brother’s blood.’

‘She has been raised by savages,’ Clarence countered. ‘Please, dear friend, I share your joy if indeed the woman is Philomena, but I also urge you to prepare yourself.’

Aloysius folded the letter, returned it to the envelope and tucked it inside his suit coat. ‘I have been preparing for this moment for twenty-three years, Clarence. My niece was born a Wade and no Indian, Geronimo or not, can ever take that away from her.’

No, Clarence thought, they can’t take a name but they can take other things.

The Great Plains Nicole Alexander

Nicole Alexander, the 'heart of Australian storytelling', takes us on a captivating journey from the American Wild West to the wilds of outback Queensland, from the Civil War to the Great Depression, in an epic novel tracing one powerful but divided family.

Buy now