- Published: 16 August 2022

- ISBN: 9780143794363

- Imprint: William Heinemann Australia

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 320

- RRP: $34.99

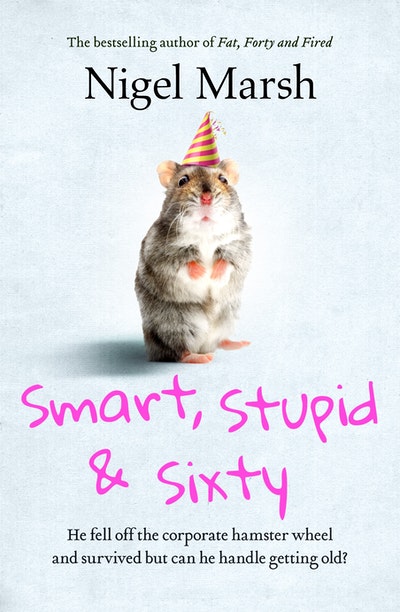

Smart, Stupid and Sixty

Extract

In early 2019 I received a call from my brother in the UK saying our mother was extremely unwell and had been taken to hospital in an ambulance. To my eyes, there aren’t many bad things about living in Australia, but . . . this is the worst. Thankfully, my brother lived with his family barely 15 kilometres away from Mum. Whilst this was wonderful for her, it did mean that Jonathon shouldered an uneven portion of the load in an unavoidably unfair division of labour.

Many of our friends in Australia have elderly parents in the ‘home country’, be it the UK, Greece, South Africa or Canada, and face the exact same issue. Increasingly so at our age, as our respective parents start to nudge ninety. A conversation with one of them – Alan – was incredibly instructive.

‘Nigel,’ he said, ‘don’t fall into the trap of attempting to plan it so you’re there, holding your Mum’s hand, when she takes her last breath.’

‘Blimey, mate, that’s exactly what I’m planning,’ I replied.

‘And that’s normal and understandable. It’s a mistake many people in our situation make.’

‘Why’s it a mistake?’

‘Because you should plan instead to spend time with her before her last moments. Meaningful time. Now. When you have the chance. Important and lovely though it is to be there at the very end, you can’t guarantee you’ll be able to arrange it so that you are. And even if you can, she might not even be conscious or aware of your presence at that stage. Think of how you can have the maximum positive impact for her. It might just be that a week when she’s well – if she gets better – is far more appreciated than the day when she’s dying.’

I thought about what I would want when, and if, I get to Mum’s situation and concluded that having my kids visit and spend time with me – proper time – would be my deepest desire. I booked flights later that evening.

Never one to knowingly do things by halves, I booked for a whole month, not a week.

. . .

21

Queen Camel 3

By the time I arrived in Somerset, Mum had been home from the hospital for three weeks and was making heroic efforts to adapt to her new routine – and reality. The terms for discharging her were that she had to have twenty-four-hour live-in care. So, it turned out I wasn’t going to live alone with my mum in her house, after all. And, indeed, therefore never would. Instead, I was going to be spending a month with Mum and Dee – Dee being the wonderful, but painfully shy, nurse who had been assigned to the task by her employer, Bluebird Care.

Mum’s cancer was myeloma. I’d never fully realised how many sub-brands the evil little fucker has. It turns out that you can basically get cancer of anything and everything. Breast, lung, brain, throat, skin, bowel . . . it’s a veritable smorgasbord. Myeloma is cancer of the bone marrow. Nice.

Mum’s cancer was currently in remission but the intensive chemo programme had knocked her for six. Myeloma is never cured. It always comes back. And when it next did, Mum had already decided, and unequivocally communicated, that she wanted no more chemo. The effects of the regime had been so uncomfortable and distressing that she knew she would literally rather die than go through it again.

As well as the cancer and the after-effects of the chemo, she was struggling with water on the heart, a poorly functioning kidney, limited mobility and anxiety attacks. An important part of Dee’s role was to correctly administer Mum a complex daily regime of drugs to help manage her various symptoms. In different doses and at varying times, Mum had to take a cocktail of pills such as Omeprazole, Rivaroxaban, Furosemide, Aciclovir and Bisoprolol. (Who names these things? It’s like they were generated by a team of people at a ‘who can score the most at Scrabble’ competition.)

Watching Mum swallow five pills, one after the other, at my first breakfast with her, I suggested that if I picked her up and shook her she’d rattle. To my delight, she smiled, then giggled. It reminded me of the laughs we’d had over the weekend at the hotel in Instow the year before. And gave me hope that I could bring a bit of light relief and enjoyment to a grim situation.

But it wasn’t really a laughing matter. Mum was struggling. Mentally as well as physically.

After that first breakfast she said to me, ‘Nidgey, I’m on my way out.’

‘Good idea, Mum,’ I replied. ‘The rain’s stopped and it looks like it’s going to be a lovely day. Would you like me to drive you or shall we go with your walker?’

‘No, silly. Not out – out out. Dying.’

She then proceeded to tell me she didn’t have anything left to live for and how her carrying on felt utterly pointless. The mood wasn’t helped by the stairlift breaking down so she couldn’t get to her room. Stairs were beyond Mum, but on the flat she could slowly – really slowly – get about with her three-wheeled walker or by cruising like toddlers do – holding onto things at waist height as she shuffled along.

It brought to mind the phrase I had recently read about the ‘divine circularity of life’. As a toddler, you’d be wobbly edging around the house holding onto things for balance whilst wearing nappies, and eighty-five years later you end up wobbly edging around the house holding onto things for balance whilst wearing nappies. Marvellous.

Later that morning, fighting jetlag, I made myself a coffee. I have to confess I’m a rolled-gold coffee addict. In Sydney I start every day with at least three cups. And over the years I’ve become a terrible coffee snob. I like my cuppa exactly to my specifications.

Visiting Mum in the past, I would drive to a local café rather than attempt to consume the unrecognisable sludge produced by the store-brand instant coffee she kept in her kitchen. Granted, it was warm and wet, but that was where the similarity with what I’d call coffee ended.

So I was pleasantly surprised to be informed by Dee that, in preparation for my stay, Mum had dug out some proper coffee. And sure enough, there in the cupboard next to an individual-size cafetière plunger thingy was a bag of high-quality ground coffee.

Surprised and impressed, I made myself a huge mug and sat down to read through the daily care notes that Dee wrote for her bosses back at Bluebird Care.

I put the lever arch file on my lap and took a sip. Yikes – I nearly spat it out across the table. Holy shit, it was revolting. It smelt like coffee, but, boy, it tasted worse than rancid arse. I went back into the kitchen to check the packet. Perhaps I’d made it wrong? Nope, there were just the usual instructions on the pack.

Hold on – what was the best-by date on the bottom? 12/02/1999. 1999?! It was almost a quarter of a century out of date.

When I asked Mum where and when she’d bought it, she said, ‘Oh I didn’t buy it. It was a gift Clive and Diana brought when they visited from Canada.’ I resisted the temptation to point out that that had been before the turn of the last century.

When I had recovered and got myself a glass of water instead, my day didn’t improve as reading the care notes reduced me to tears. Mum was clearly trying so hard but struggling to cope, God love her.

Atul Gawande, in his superb book Being Mortal, discusses how we as a society have to learn to better deal with the elderly in their last years. We shouldn’t treat dying as an illness to be cured; instead, focusing on quality of life. Changing the goal from helping people extend their last years to helping people enjoy their last years.

I made a promise, there and then, that this was what I would strive to do. And made a mental note that checking the best-by dates on the food in her larder might not be a bad first step in the process.

Smart, Stupid and Sixty Nigel Marsh

From the bestselling author of Fat, Forty and Fired comes this humorous, thought-provoking, poignant and life-affirming account of turning sixty.

Buy now