Tara June Winch discusses the creation of her 2019 novel The Yield, and the power embedded in Indigenous language.

I was born on Ngurambang – can you hear it? – Ngu–ram–bang. If you say it right it hits the back of your mouth and you should taste blood in your words. Every person around should learn the word for country in the old language, the first language – because that is the way to all time, to time travel! You can go all the way back.

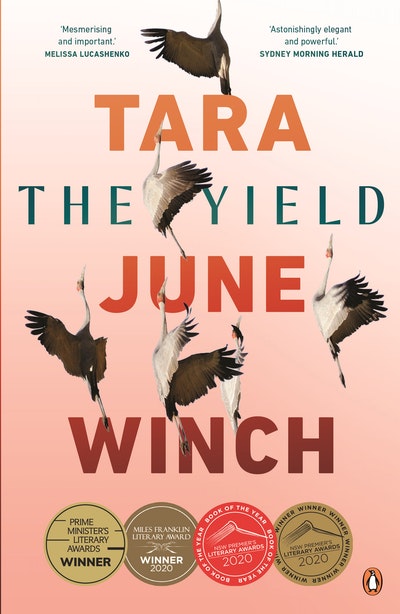

Tara June Winch’s 2019 novel The Yield begins with Wiradjuri elder Albert ‘Poppy’ Gondiwindi introducing his story. Facing death, he’s determined to pass on to the next generations the language and knowledge he’s amassed throughout his life on the banks of the Murrumby River. So, he’s decided to construct a dictionary of all he remembers – all the words he ‘found on the wind’. Embedded in every one of his definitions are personal reflections and wisdom passed down from the ancestors. And via the scattering of these dictionary entries throughout the book, we’re revealed interwoven storylines of people and country through time.

Winch traces the beginnings of The Yield back to researching her 2006 novel Swallow the Air. In order to bring some Wiradjuri language into that story, she studied the dictionary compiled by Dr Uncle Stan Grant Snr AM and linguist Dr John Rudder. ‘I really enjoyed that process,’ she says. ‘Then I knew I wanted to incorporate the language into another novel – the next one, which I thought wouldn’t take very long. So all those years it was in the back of my mind.’

The driving force behind the process was Winch’s desire to create something for her father, honouring the language he’d never known as a child. Whether in her now home of France, in Australia or further afield, over the years she collected various threads to be one day woven into the fabric of the book. There was a locust storm while driving to Wagga Wagga, leading her to contemplate the implications of Australian wheat farming – and the idea of placing the story inland. Then the 2005 Australian Wheat Board Iraqi kickback scandal led her to an internship in New York, investigating the concept of ‘dirty wheat’. While in the USA, she also interned at the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. And, more recently, watching her own daughter grow up speaking French and English opened her mind to the power of bilingualism.

It was during conversations with her mentor, Nobel Prize-winner Wole Soyinka, that Winch describes discovering the ‘groundwater’ of the book. ‘I think when you decide on something that you really, really want to write about you will carry it until it’s done,’ she says. ‘I don’t think time really matters. It just sits there and you know it’s there, and you can keep adding to it. During my mentorship with Wole Soyinka, it was something that we discussed not in the form that it is now, but the essence of it. It was still about translation and language, but we explored concepts of the power of the tongue... We looked at a lot of traditional stories for their simplicity and their ability to time travel, as well as their use of metaphor and proverb.’

Winch’s methodical gathering of ideas is apparent in The Yield’s thematic layering. The book is at once a meditation on grief and shame, greed, environmental degradation, the continuing aftershocks of white colonisation, and the cultural poverty we all inherit as a result of the dispossession of Indigenous people and culture. But it is also a celebration of rediscovering ‘home’, the healing powers of family, finding purpose; as well as honouring what was, preserving what remains and reclaiming Indigenous language, storytelling and identity for the future.

After so many years of contemplation, Winch says the writing came fast. ‘So much of writing for me is sitting and staring at a tree, or daydreaming about the characters and the concept. Once I was at a point where I had it, then it was just a huge exorcism, I guess, to get it out. It was all coming out really, really fast at that point.

‘It’s like it ripped my heart out, writing the book. It physically changed me. I morphed into another person. I put on 35kg really fast, because of my commitment to sitting at it, and not leaving it once it was there. To capture all of that, it had to happen fast.’

Despite the vast geographical and chronological distances between conception and creation, some sentences survived the journey from a very early stage. Others proved more elusive. ‘There’s a sentence in the book where August comes home, which I wrote in France,’ Winch continues. ‘There’s a moment where she listens to the sounds you can hear in the bush, the country – cicada friction and bird whip. It seems like a throwaway idea, but does that say anything to you about the bush in Australia? To get those few words took ages. Living in France, that sound doesn’t exist in the bush here – it’s different. So, I listened to YouTube. Amateur birdwatchers put videos up there that are hours and hours long. So, even when I couldn’t get to Australia, I found a way to get there.’

With a French translation of The Yield on the horizon, Winch is interested to see how the mechanics of the book will be interpreted. It’s a complex structure – multiple perspectives revealed via Poppy’s dictionary entries, his grand-daughter August’s experiences of returning home after years abroad, and the 19th century letters of a Lutheran missionary. Each of Poppy’s chapters contain Wiradjuri words translated to English from his alphabetically backwards dictionary; every passage encompassing a story in itself, which, when told in order, reveal greater narratives of past, present and future. But while the French translator has a monumental technical challenge ahead of them, Winch trusts that a European audience will embrace the subject matter wholeheartedly. Though shamefully, in Australia, celebrating the wondrous cultural significance of the oldest continuous human civilisation on Earth is still far from a national pastime. The difference, Winch believes, is education.

‘French people are increasingly interested in Aboriginal history, culture and our writers,’ she continues, adding that the French embrace their own artefacts – like the 20,000-year-old rock art found within the Lascaux Caves – as an enormous source of national pride. ‘People travel from all over the world to come and see this rock art. And the way that they’ve respected this rock art – the level of funding that goes into it… It’s of utmost importance to French people.

‘It’s like how kids get taught about the Greeks when they’re young – Hercules and all those kinds of things. We’ve got all those warrior stories and amazing stories right in our backyards. It’s about changing everybody’s concept of themselves as a nation… I have faith that the Australian identity will embrace our collective history. But it’s not there now. Really, the simplest way to change the next generation is to introduce early Indigenous language education. To have it in schools is so important. It’s just as important as English or mathematics.

‘Before I go overseas, one of the things I do is to learn some words of the language spoken in the country I’m going to. There’s two reasons I do this. One is for practicality. And the other is respect. To see someone’s face light up because you’ve tried. Even if you mess it up. We’re living on other people’s countries in Australia. So, why not come at our First Nations’ languages from a place of respect.’

Of all of the words in the Wiradjuri dictionary, it’s yindyamarra (‘respect’) that Winch likes most. And like so many of the words Poppy introduces throughout the book, its literal translation to English doesn’t at all capture the complexities of the word in an Australian context. ‘Yindyamarra is “respect” and “gentleness” and “kindness” all in one,’ she says. ‘Respect on its own is so harsh. There are corners to that word.’

As Poppy explains it: I think I’ve come to realise that with some things, you cannot receive them unless you give them too. Unless you’ve even got the opportunity to give and receive. Only equals can share respect, otherwise it’s a game of masters and slaves – someone always has the upper hand when they are demanding respect. But yindyamarra is another thing too, it’s a way of life – a life of kindness, gentleness and respect at once. That seems like a good thing to share, our yindyamarra.